No one knows exactly how options first emerged. However, contracts similar to options have been around for thousands of years. Insurance is, in fact, a type of option. The insurance buyer pays a premium to the insurance writer in exchange for a loss-covering promise. This transaction is similar to a put option, which provides coverage of a portion of losses on the underlying and is often used by holders of the underlying.

In this lesson we provide a brief overview of the structure of the global options market. We start by discussing the over-the-counter options market which existed in the United States in the early twentieth century. We then discuss the emergence of the exchange-listed options market driven by the establishment of the Chicago Board Options Exchange in 1973. Our discussion of the latter includes an introduction to the terms, trading mechanics as well as the regulation of of exchange-listed options.

This reading is part of our introductory options course. Please check out the full overview of lessons here.

1. Over-the-Counter Options Markets

Customized over-the-counter options markets existed in the United States in the early twentieth century and lasted well into the 1970s. A collection of enterprises known as the Put and Call Brokers and Dealers Association operated as brokers and dealers. They worked as brokers, attempting to match buyers and sellers of options in order to earn a commission. They offered to accept either side of the option transaction as dealers, usually by hedging the risk in another transaction. The majority of these transactions were retail, which meant that the general public was their customers.

The establishment of the Chicago Board Options Exchange was a revolutionary event, but it effectively killed the Put and Call Brokers and Dealers Association. As a result of the increased usage of swaps, the bespoke over-the-counter options market was reborn. Currency options were in high demand, as they were a natural extension of currency swaps. Interest rate options developed later as a natural extension of interest rate swaps. Bond, equities, and index options began to trade in a thriving over-the-counter market soon after.

However, unlike the former over-the-counter options market, the present one has mostly become a wholesale market. Institutions and companies are the most common parties involved in transactions, and individuals are rarely involved. Dealers offer to take either a long or short position in options, hedging the risk with transactions in other options or derivatives, similar to the forward market. The buyer is exposed to credit risk because there are no guarantees that the seller will meet its obligations. As a result, option purchasers must assess the credit risk of sellers and may seek risk mitigation measures such as collateral.

All of the terms of customized options are specified by the two parties, including the price, exercise price, time to expiration, identification of the underlying, settlement or delivery terms, contract size, and so on.

Over-the-counter options markets, like forward markets, are largely unregulated. Participating institutions, such as banks and securities firms, are normally regulated by the proper authorities in most countries, while the over-the-counter options markets are rarely regulated. There are, however, regulating agencies for these marketplaces in some nations.

2. Exchange-Listed Options Markets

In 1973, the Chicago Board Options Exchange was established. It was the first organization to offer a market for standardized options, having been founded as an extension of the Chicago Board of Trade. Standardized options are also traded on the NYSE American and Nasdaq in the United States. Standardized options are widely traded on exchanges around the world, such as Eurex and Euronext and most major foreign exchanges.

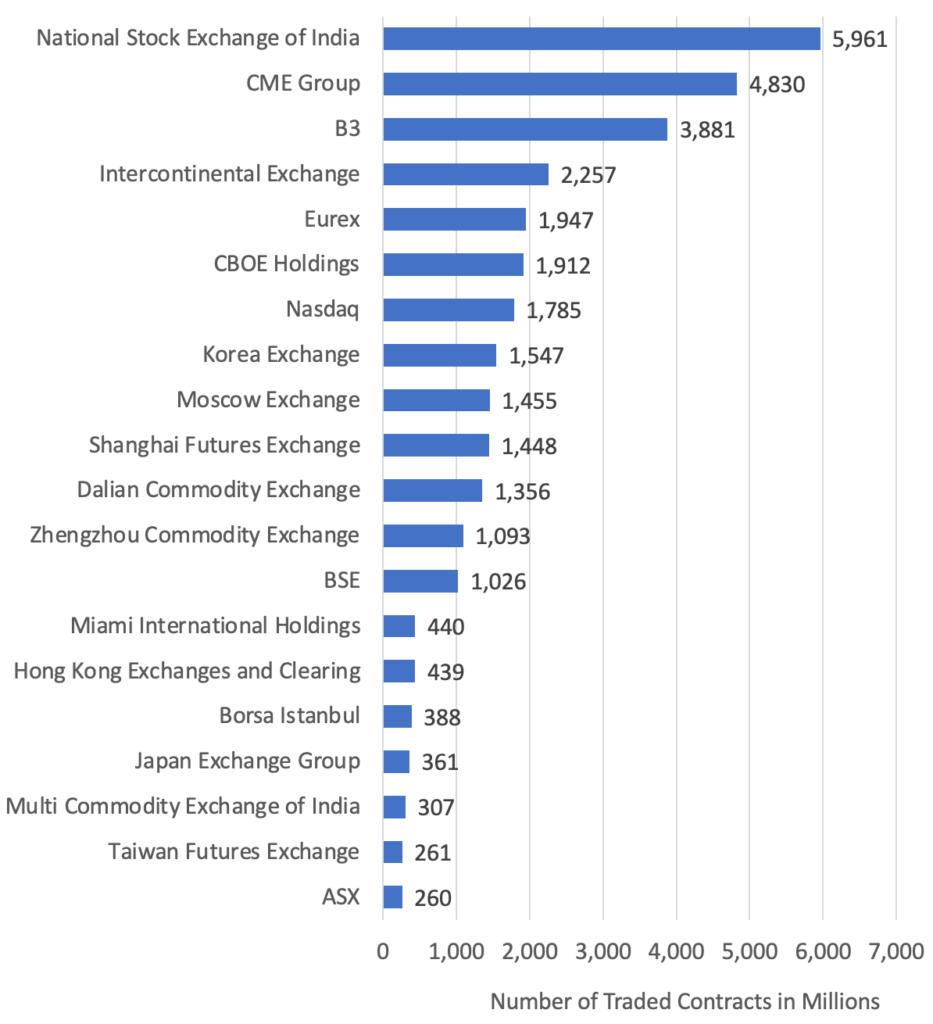

The below Exhibit shows the 20 largest derivatives exchanges in the World.

Exhibit: List of Largest derivatives exchanges worldwide in 2019, by number of contracts traded (in millions)

2.1 Terms of Exchange-Listed Options

Except for the price, the exchange sets all terms of standardized instruments for options. As a result, the exchange sets the expiration dates, exercise prices, and minimum price quotation unit. The exchange also specifies if the option is European or American, whether cash settlement or delivery of the underlying is required, and the contract size. An option contract on an individual stock in the United States covers 100 shares of stock. One option contract, which is actually a collection of options on 100 shares of stock, is often referred to as “one option”.

The contract size for index options is expressed in terms of a multiplier, which indicates that the contract covers a hypothetical number of shares, as if the index were a single stock. Similar specifications apply for options on other types of underlyings.

Trading in exercise prices that are close to the current stock price is normally permitted on the exchange. Options with exercise prices around the current stock price are generally introduced as the stock price moves. The vast bulk of trading takes place in options that are close to being at the money. Deep-in-the-money and deep-out-of-the-money options are options that are far in the money or far out of the money. They are rarely traded and are sometimes not even posted for trading.

The majority of exchange-listed options have relatively short expiration dates, usually the current month, the following month, and sometimes one or two further months. The two shortest expirations are where the majority of the trade takes place. Long-term equity anticipatory securities, sometimes known as LEAPS, are listed on several markets with expirations of several years. Although these options are widely traded, most investors choose to buy and hold them rather than trade them as frequently as shorter-term options.

The exchanges also determine on which companies they will list options for trading. Although there are some specific conditions, the exchange will normally list the options of any company for which it believes the options will be actively traded. The corporation has no say in the situation. A company’s options may be listed on more than one exchange in the same country.

2.2 Trading Mechanics of Exchange-Listed Options

Although it is becoming a rarer sight, some exchanges have pit trading, whereby parties meet in the pit and arrange a transaction. Electronic trading, in which transactions are carried out via computers, is used by several exchanges. In either situation, the clearinghouse guarantees the transactions. The Options Clearing Corporation, or OCC, is an independent company in the United States that serves as the clearinghouse. If the seller defaults at exercise, the OCC assures the buyer that the clearinghouse will step in and complete the commitment.

The seller of an option must post some margin money, which is based on a formula that reflects whether the seller has a position that hedges the risk and the option is in- or out-of-the-money. If the price moves against the seller the clearinghouse will force the seller to put up additional collateral. Despite the fact that defaults are uncommon, the clearinghouse has always paid when a seller defaults. As a result, exchange-listed options are effectively free of credit risk.

Exchange-listed options can be bought and sold at any time prior to expiration due to the standardization of option terms and participants’ universal acceptance of these conditions. As a result, a person that buys or sells an option can re-enter the market before the option expires and counterbalance the position by selling or buying an identical option. From the clearinghouse’s perspective, the positions cancel.

Traders on the options exchange, like those in futures markets, are either market makers or brokers. There are a few minor technical differences between different types of market makers in different option markets, but they are minimal. Option market makers, like futures traders, try to profit by scalping (keeping positions for a short period of time) to gain the bid—ask spread and occasionally maintaining positions for longer periods of time, closing or leaving them open for days or weeks.

The holder of an option determines whether or not to exercise it when it expires. There are no further benefits to waiting when an option is about to expire, hence in-the-monev options are always exercised if they are in-the-money by more than the transaction cost of purchasing or selling the underlying or arranging a cash settlement upon exercising.

If a stock is trading at $160 at expiration, the calls with an exercise price of $150 will be exercised. The majority of stock options traded on exchanges require actual stock delivery. As a result, the seller delivers the stock, and the buyer pays $150 per share to the seller through the clearinghouse. If the contract stipulates that it is to be settled in cash, the seller simply pays the buyer $10. The buyer tenders the stock and receives the exercise price from the seller for puts that require delivery. If the option is out of the money, it will simply expire without being exercised and will be removed from the books. If the put is settled in cash, the writer pays the buyer the same amount in cash.

Some non-standardized exchange-traded options exist in the United States. Some exchanges, in an attempt to compete with the over-the-counter options market, allow some options to be individually designed and traded on the exchange, taking advantage of the clearinghouse’s credit guarantee. These options are typically only accessible in large sizes and are only traded by large institutional investors.

2.3 Regulation of Exchange Based Options Markets

Options markets that are traded on exchanges are usually regulated at the federal level. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is responsible for federal regulation of options markets in the United States; comparable regulatory frameworks exist in other countries.

Previous Lesson:

<<< Introduction to Option Contracts

Next Lesson:

The Most Common Types of Options >>>

0 Comments